Copyright Susan Fleet 2007 All rights reserved None of the materials on this website may be reproduced or

transmitted by any means, including photocopying, recording or the use of any retrieval system without

permission. For permission, email Susan via the contact page

Each family lived in large barracks with no partitions, no stoves and no running water. The 30,000 children who

lived in the camps attended school there. [J-3]

DEPORTED

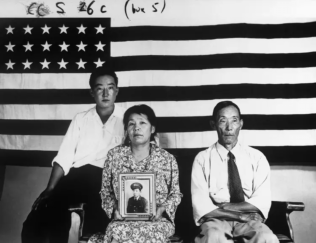

But many Japanese-American men and women joined the U.S. military to defend the country of their birth and served with

distinction. Below in their uniforms. At right, two parents sit in front of an American flag with their high school age son;

the mother proudly holds a framed photo of their other son in his military uniform. [J-4]

,

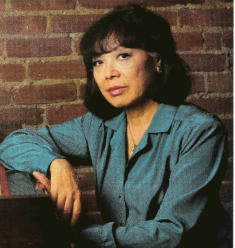

Toshiko Akiyoshi

(1929 -- )

Jazz Pianist, distinguished Composer,

Big-band leader, NEA Jazz Master

From Riches To Rags

The youngest daughter of wealthy Japanese parents, Toshiko was born in 1929 in Darien, Manchuria, a part of

mainland China then ruled by Japan. Her father owned several textile and steel mills. At the age of seven, Toshiko

began studying Western classical music on piano and fell in love with the instrument. Her father, disappointed at having

four daughters but no son, expected her to become a doctor. But World War II intervened. [1] See sources below

After Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, many believed the United States would be targeted next. At that time

125,000 men, women and children of Japanese heritage lived in the United States. More than 60% of them were

United States citizens. Many of them (Issei) had come to America decades earlier and clung to their native language and

customs. But their American-born children (Nisei) spoke English and attended American public schools. [J-1] See sources below

In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order forcing more than 10,000 Japanese Americans

into internment camps. No charges were filed against them and no hearings were held to find evidence of subversion.

At left, a Japanese family arrives at internment camp:

photo by Dorothea Lange.

At right, a young Japanese girl clutches her doll.

At the end of the war in 1946, Toshiko, her three sisters and their parents were deported to Japan, penniless, carrying

only what fit into their suitcases. Her father’s businesses had been confiscated. [2] They settled in Beppo City in southern

Japan. U.S. soldiers were were everywhere. One day, seventeen year old Toshiko saw a sign in the window of a dance hall

for soldiers. PIANIST WANTED. She spoke to the manager, who said he needed a pianst for the dance band and asked her to

audition for the job. She played a Beethoven piano sonata. Impressed, he told her to begin at six o’clock that night. [2]

Toshiko hated the dance-band arrangements, but loved having access to a piano. During the afternoon, she practiced

classical repertoire on the club piano and began to think about a classical music career. But when her father found out

about her job, he was angry and they argued. He finally allowed her keep the job, but only until she began medical school.

One night a Japanese record collector heard the band and told her she had the potential to become a great jazz pianist.

He played a recording of jazz pianist Teddy Wilson for her. Wilson’s rendition of “Sweet Lorraine” was a revelation.

“When I heard it,” she said, “I knew I wanted to play like that.” [3]

Hear Teddy Wilson play Sweet Lorraine

She spent hours notating music she heard on jazz recordings and began writing her own charts. “My whole life was jazz

during those years, so I became an adult through jazz music.” In 1950, against her family’s wishes, she left Beppo City

and moved to Tokyo.

Conditions were dire in postwar Japan. Firebombings had destroyed the wood-frame homes owned by most Japanese.

Thousands of Japanese citizens lived in railroad stations and public parks. Japan’s fishing fleet had been decimated by the

war and food was scarce. Former President Herbert Hoover, who served during the Great Depression, chaired an

advisory committee that recommended 800 million tons of food be sent to Japanese citizens. [J-3]

The 1950s Bring Recognition for Toshiko

In Tokyo, Toshiko formed her own group and worked on her improvisation skills by listening to recordings for hours.

Bud Powell, a be-bop pioneer in the 1940s, became her biggest influence. In 1953, pianist Oscar Peterson came to

Japan to play a “Jazz at the Philarmonic” concert produced by Norman Granz.

Peterson heard Toshiko play and urged Granz to record her.

Toshiko’s Piano was an overnight success in Japan. By 1955, she was Japan’s

leading jazz pianist, the highest paid jazz musician in Japan. But she said,

“I knew that I had to come to the States to get better as a jazz player.” [1,2]

Including a copy of Toshiko’s Piano, she applied to Berklee College of Music in Boston.

Berklee president Lawrence Berk offered her a full scholarship and paid for her plane ticket to Boston. [5]

During her first semester at Berklee in 1956, she sat in with Bud Powell’s trio at Storyville, a nightclub owned by

influential jazz promoter George Wein. Two months later she was playing there four nights a week. That summer she

performed at the Newport (RI) Jazz Festival. [8]

But much of the attention she drew was based on her race and gender. She appeared

on the television show “What’s my Line” playing be-bop piano in a Japanese Kimono.

A 1957 Time Magazine article touted her playing as some of the best jazz piano around.

A press agent advised her to wear a kimono all the time because she was “the only

female jazz pianist from Japan.” [6]

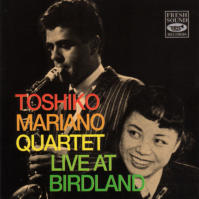

Then she met Charlie Mariano, a promenent jazz saxophone player who had performed

with the Stan Kenton Band. He admired her talent and they began a relationship.

In 1959 they married; they performed and record albums as the Toshiko-Mariano Quartet.

The 1950s and the Impact of Television

In 1950 only 5 million homes in the United States owned a TV set.

By 1955, more than 55 million homes had one.

People watched Elvis Presley on TV.

And movies starring Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell.

Rock music dominated the airwaves and musical tastes changed.

The popularity of jazz and big bands declined.

The 1960s: Hard times on two continents for Toshiko

For much of the 1960s, Toshiko divided her time between Tokyo and New York City. Between 1963 and 1965 she toured Japan and

Europe with small jazz combos and performed as a jazz piano soloist with Japanese symphony orchestras. In 1964, Charles Mingus

featured her with his big band in a Town Hall concert in New York. [7] Her interest shifrted to composing music for big band.

“I wanted to hear more colors,” she said, “in order to express my musical and philosophical attitudes through jazz language.” [5]

In 1964 her daughter, Michiro Mariano, was born in Japan. But in 1967, her marriage to Charlie Mariano ended. She played solo piano gigs at

NYC jazz clubs. “It was hard to be a single mother supporting myself as a jazz musician,” she said. “I went from 1963 to 1972 wondering how

I would pay my rent, but some job or another always came along. Somehow I survived.” [4]

The 1970s: Acclaimed recordings in Japan

In 1972 they moved to Los Angeles and Tabackin joined Doc Severinson’s band on The Tonight Show. The couple recruited musicians for

a “workshop” big band that rehearsed weekly, and Toshiko’s portfolio of big band charts grew. But producers and club owners wanted smaller,

less expensive ensembles. Toshiko decided to record her big band charts with the workshop band. Again she turned to the Japanese

community for financial backing. She raised enough money to record the band in a small studio in Los Angeles in 1974. [1,2]

A Unique recording: Kogun

Kogun (loosely translated one man army) was inspired by a news article Toshiko read.

A Japanese soldier had been discovered hiding in a cave in the Philippines,

believing that World War II had not yet ended. The soldier finally emerged from

the cave and surrendered his sword.

With its blend of Japanese traditional instruments and big band jazz, Kogun became one of Japan’s biggest all-time hits, selling 30,000 copies

upon release and tens of thousands more thereafter. Listen to the title track. It begins with traditional Japanese instruments and morphs into

big band swing. And ends with Japanese instruments.

Kogun and her subsequent recordings established Toshiko’s reputation not only as a big band composer, but also as an arranger and conductor.

In 1976 the Akiyoshi-Tabackin Big Band placed first in a Downbeat critics poll. Long Yellow Road was named best album of the year by

Stereo Review Magazine. Insights was Jazz Album of the Year in Japan.

In 1978, for the first time in the history of jazz, a woman received top honors in the categories of jazz, composer-arranger and big band.

Downbeat critics selected Insights as Record of the Year, Toshiko won first place as jazz arranger and her big band was voted number one.

By 1980 the Toshiko Akiyoshi--Lew Tabackin Big Band was considered one of the most important and influential big bands in jazz.

Since 1976, Toshiko’s big band albums have received 14 Grammy nominations.

The 1980s and 1990s: Critical success, financial struggles

Lew Tabackin left The Tonight Show band in 1982. The couple moved to New York City

and formed The Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra, featuring Lew Tabackin.

But Toshiko still had to tour with small combos or play solo piano gigs to raise money for the band. Their recordings were big hits in Japan,

but the only albums available in the United States featured Toshiko on solo piano or in small combos.

A New Century and a New Composition

In 1999 a Buddist priest asked Toshiko to compose a piece for Hiroshima, and sent her photos taken three days after the bomb was

dropped. “The photos were so awful, people losing skin and so on. It was a great shock to me. I had never seen anything like this. I

really didn’t see the meaning of writing about something so tragic and so horrible.” [5]

But later, after reviewing the photos again, she found one she hadn’t noticed, “a woman who was underground and wasn’t affected

by the bomb and … this photo was beautiful.” The woman’s faint smile of hope inspired her. “This is not about America and Japan.

It could be anyplace. We don’t want atomic weapons. The Hiroshima people still have hope for a better future.” [5]

Her three-part suite, Hiroshima: Rising From The Abyss, had its premier in Hiroshima

on August 6, 2001, the 56th anniversary of the bombing,

and scant weeks before the September 1, 2001 attacks on the United States.

“It was an emotional concert,” Toshiko said. “Some musicians told me how proud

they were to be associated with the organization. It was a great performance.

I actually cried on the stage because Lew plays so beautifully on the last piece.” [5]

NEW DIRECTIONS AND IMPRESSIVE HONORS

NEW DIRECTIONS and a REVELATION

WELCOME TO SUSAN FLEET’S WEBSITE

AUTHOR, TRUMPETER, MUSIC HISTORIAN

In December 2003 the band played its last concert at Birdland in New York, where it had played every Monday night for more than

seven years. Toshiko wanted to get back to her first love, piano. “I’m 74 years old,” she said, “and I think I can get better. Thats the

wonderful thing about jazz. There is no end. There is always something to perfect.” [8]

In 2007, Toshiko’s extraordinary talent and multifaceted career won recognition

from the National Endowment for the Arts, which deemed her a “Jazz Master”

its highest honor in Jazz. Of the six honorees, Toshiko Akiyoshi was the only woman.

As her father had predicted many years earlier, she achieved great success.

But as a musician, not as a doctor.

In 2018, Toshiko receved the Mellon Jazz Legacy award, in Seoul, South Korea. Watch her play here

At this writing, Toshko and her husband Lew Tabackin currently live in New York City.

Photo at left Tsutomo

SOURCES: Toshiko Akiyoshi

1. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen, Linda Dahl, 1984

2. “Toshiko Akiyoshi: Jazz Composer, Arranger, Pianist, and Conductor,” Laura Koplewitz, The Musical Woman, Vol II (1984-1985)

3. “Jazz is Her Way of Life,” Bryna Taubman, NY Post, 4 October, 1967, quoted by Koplewitz

4. “The First Lady of Jazz: An Interview with Toshiko Akiyoshi,” Matt Weiers, Allegro, an AFM Local 802 Publicaton,

Vol CIV No. 3, March 2004

5. AllAboutJazz.com: “A Fireside Chat with Toshiko Akiyoshi,” Fred Jug, 2003

6. Time Magazine, “Jazz Import,” August 26, 1957

7. Berklee Today, “Toshiko’s Odyssey,” Mark L. Small, Spring 1993, Vol IV, #3

8. Berklee News, “Playing Shape,” Ed Hazell, June 2, 2004

9. “A Hub homecoming for Akiyoshi,” Bob Blumenthal, Boston Globe, 10-16-1992

Historical Sources on Japanese-American Internment and post WWII Japan

J-1. Years of Infamy:The Untold Story of American’s Concentration Camps, Michi Weglyn (1976, 1996) University of Washingon Press.

J-2. This Fabulous Century: 1940-1950, Time-Life, Vol. 5, 1969

J-3. Studyworld,com: American Occupation of Japan

J-4. Infoplease.com:Japanese Relocation Centers, Ricco Villanueva Siascoco & Shmuel Ross

© copyright 2024 Susan Fleet

[J-2]

Although Toshiko won critical acclaim and her talent was recognized by top jazz musicians like Charles Mingus, John Coltrane and Art Blakey,

she remained largely unknown. In 1966, she decided to give a concert in Town Hall to attract attention. The format would feature trios with

Toshiko on piano, and a grand finale premier of her compositions for big band. To finance the concert Toshiko went door-to-door to solicit

money from the Japanese business community. “They will only buy if I come to them in person. I spent my days going to businessmen

(to sell tickets) and my nights working on my music. It is very tiring, but it must be done this way. Otherwise it is not proper.” [2]

Her 1967 Town Hall concert was a critical success, but rehearsing and performing left no time to write big band charts.

Then her life took a dramatic turn. She met versatile jazz saxophonist Lew Tabackin. He recognized her potential and

encouraged her to continue writing. They began a personal relationship and married in 1969.

1946--1950: Postwar Japan